In Cantillana, people are affiliated through their mothers to the cult of the Virgin Asunción or the Virgin Pastora. This matriarchal social life gives rise to two clans that fervently organise themselves around exceptional processions. This art has always brought the clans together. Women practise it alone or in groups, in their living rooms, on their balconies, in the evening in front of their houses or after dark in one of the village squares, to the rhythm of joyful and lively conversations.

Today, it continues to be passed down from mother to daughter. For most women, it is a hobby, a marginal practice, often reserved for long summer evenings or during holiday periods. For gypsy women, it is a source of additional income at any age. Once a pillar of the local economy, only part of the production of enrejado shawls continues to be made in the village by craftswomen. This craft activity is the most characteristic of Cantillana. The women who practise it enable the whole of Andalusia and beyond to continue this tradition by wearing a shawl at ferias.

They were initially manufactured in China, mainly in Canton, by specialist embroiderers. The first designs were embroidered with dragons, peonies and other traditional Chinese motifs. Produced specifically for export, these shawls were destined for Spanish colonial markets. The goods were transported by sea and land, crossing the Pacific and then the Atlantic, before arriving in Spain. This trade network operated between the 16th and early 19th centuries.

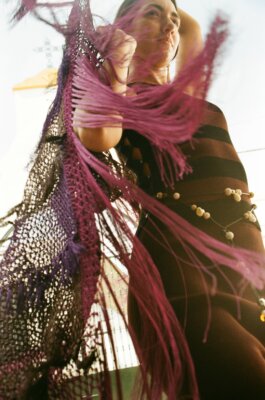

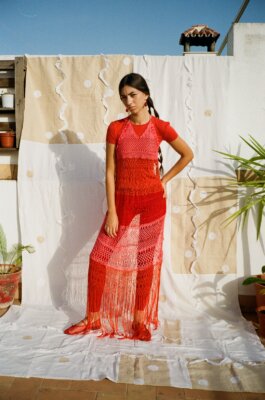

Over time, the embroidered motifs adapted to Spanish tastes. Realistic flowers such as roses and carnations, as well as peacocks and symmetrical compositions, replaced Asian symbols. From the 19th century onwards, part of the production was located in Spain, particularly the finishing touches: the long hand-knotted fringes, called enrejado de flecos, were made by Andalusian craftswomen. The mantón then became a fashion accessory and a powerful cultural symbol, worn in flamenco, religious processions and traditional Andalusian festivals.

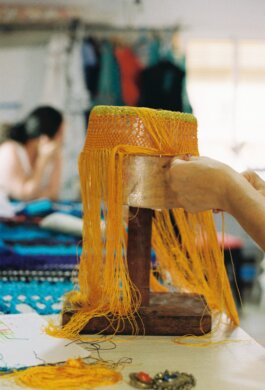

Accustomed to linear compositions, the craftswomen learned to knot it strip by strip to create a surface large enough to become a garment. They developed a circular knotting technique to meet the constraints of clothing and accessory shapes. The hat, the first piece designed using this method, embodies this shift from ornament to volume.

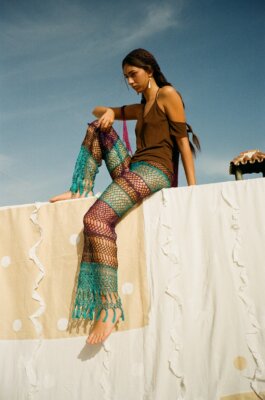

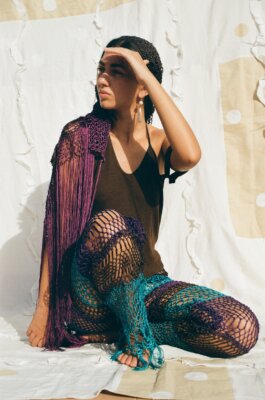

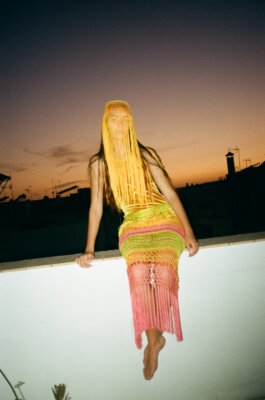

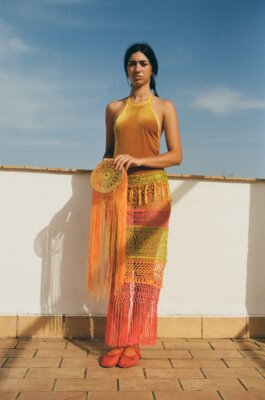

Each piece is the result of a creative dialogue between Caroline and the craftswomen. The craftswomen chose the knots, the patterns, and their stories. Each pattern is codified: it has meaning, it tells a story. Caroline provides the patterns, a colour palette, and suggests a striped pattern. Together, they rework the design of the pieces so that they are suited to both the technique and the desired shape of the garments.

Handcrafted, the enjerado borders Manila shawls, extending the fabric with knots and fringes made of silk threads. Once poured onto the fabric, the silk threads are knotted, intertwined and crossed in various ways to form different designs, grids, flowers and geometric patterns. The centuries-old tradition of Cantillana is evident in the vast repertoire of knots. Each knot has a name and a meaning, such as jazmín (jasmine), piña (pineapple), alegría (joy), corbata (tie) and almendrón (almond), giving an indication of the size, style and assembly of the threads used. The knotting is done by hand. Only a small hook, rarely used, helps to pass each knotted thread. This embellishment technique is finished with fringes of varying lengths. Flamenco dancers play with them, punctuating their movements with the clapping of the fringes against each other and against their bodies.

For two weeks, the women made the pieces. The patterns were first sent to Nuria's workshop in the village centre. From there, they were distributed to the women. The week was punctuated by trips back and forth between the workshop and the women's homes. Once each part was completed, it was collected from Nuria's workshop for assembly. This was the first time they had faced a new technical challenge: how to tie these rows of knots? The ancient technique had moved into new territory, gaining in freedom.

This edition was made possible thanks to the support of Fonds de Dotation Compagnon and Sessùn.

The Compagnon Endowment Fund provides financial support to creators, researchers and professionals in the fields of fashion and culture through projects of general interest. The endowment fund's website serves both as a showcase for its activities and as a space for reflection on fashion and current events, highlighting its unique Franco-Mediterranean perspective.

Sessùn is a fashion brand that combines creativity and commitment. Founded on values of authenticity and sustainability, Sessùn strives to promote ethical practices while creating collections inspired by artistic and cultural influences. The brand is committed to supporting initiatives that promote craftsmanship and responsible production, thereby contributing to a more conscious and environmentally friendly fashion industry.

We would like to extend our warmest thanks to Nuria Chaparro, whose expertise and commitment were instrumental in bringing this project to fruition. Founded in 2010, the company is dedicated to the artisanal production of embroidered shawls that bring flamenco culture to life. Thanks to her support, the process went very smoothly, making this collaboration all the more rewarding.

A big thank you to the artisans, Doroles Aparicio, Marie Carmen de la Hera Sole Barrios, Mari Conchi, Carmen Domingue, Asuncion Marroco, Amada Maya, Antonia Maya, Araceli Maya, Dolores Maya, Juana Maya, Consuelo Muñoz, Elisabeth Ortiz, Mari Tinoco and Mili Vega.